The Inverted Yield Curve

What is It and What Does it Tell Us? ... Trouble Ahead?

Most of us have that funny feeling that the economy is about to break, that it’s only a matter of time. Well, I, for one, consider it already broken. But there is one key indicator that can tell us something nasty is afoot — the inverted yield curve.

What is an Inverted Yield Curve?

Typically, yields of long-term fixed-income securities are higher than those of short-term securities. For example, a 10-year bond will generally have a higher yield than that of a 2-year bond. The reason for this is the obvious risk of long-term investments. The market tends to price long-term bonds lower such that they yield more than short-term bonds. This incentivizes investors with greater returns for taking a longer-term risk. The future is uncertain, especially in a world full of central banks that continuously destroy the value of their currencies and generate the boom-and-bust cycle.

But every so often, the yields on long-term securities become lower than those of the short-term securities. This causes the difference (the spread) of the long-term bond’s yield minus that of the short-term bond to go negative. When the spread goes negative, the yield curve is said to be inverted.

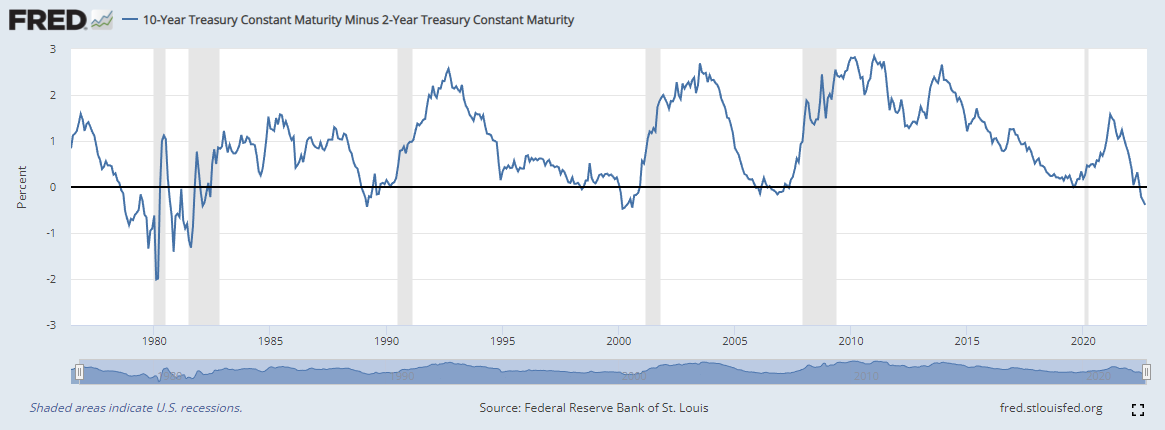

This hasn’t happened very often as you can see by the following historical trend in the 10-year minus 2-year US Treasury bond spread.1

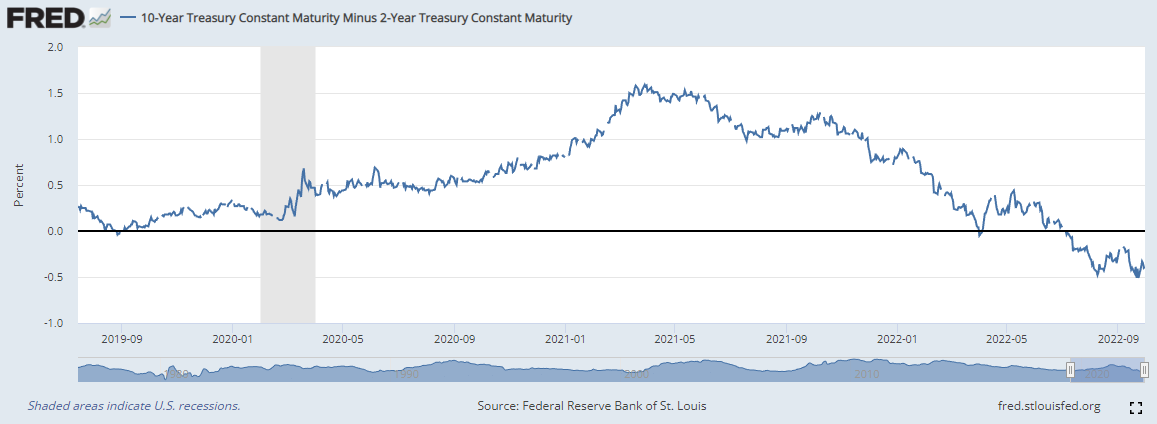

Note that those vertical gray bars indicate historical recession periods. Preceding each recession was an inverted yield curve (i.e., the yield spread turned negative). Every. Single. Time. Zooming in on this same chart to focus on the last two years (see below), we can see that we touched negative territory back in April of this year and are now firmly in the inverted zone.

Of course, technically the US economy is already in a recession regardless of the word games the government tries to play to deny reality. But the feeling of a true recession has not quite registered yet in the minds of the masses. We are just in the beginning stages. It’s not until a crash occurs that people start to realize that the cat was in the bag the whole time, and that bag was in the river.

What Causes Yield Inversion and What Does it Mean?

Let’s take a look at the 10-year yield vs. the 2-year yield side by side (see below). The red line is the long-term yield (10-year Treasury) and the blue line is the short-term yield (2-year Treasury). You can see that the long is less than the short, therefore the spread (long minus short) is negative.

Note that both curves are increasing. But it is clear that the main driver of the negative spread is the short-term rate spiking upward past that of the long-term. What is going on?

The causes of the short-term rate climb must either be due to a decrease in the supply of loanable money or an increase in demand for short-term loans (or both). You’ll see that it is likely both phenomena that are driving up the rate.

First, let’s look back starting in early 2020. You can see that the short-term rates collapsed and ran at near zero for almost a year. The yield curve was normal during this period (long term rates were higher than short term rates). But there was nothing “normal” about it really. The Fed was pushing down the short-term rate to artificially expand credit, increasing the money supply.

An artificial expansion of credit tends to cause a shift from savings towards consumption and misdirects capital. It distorts the economy and causes malinvestment. It sends a false signal that there are more resources available than there really are.

For example, homebuilders will, no doubt, bite on the low loan rates and begin building. But no one really knows how many resources (e.g., laborers, concrete, machinery, etc.) are available because the market is distorted. The artificially low rates make it seem like resources are limitless. So, in the case of home builders, they pour into the market and suck up the supply of resources, driving the prices of those resources up. As prices climb, short-term loans must continue to become available, otherwise the home builders will have to stop before the houses are complete. So, builders likely find themselves borrowing more short-term money at increasing rates in order to complete their projects, albeit at lower returns than originally expected. What happens when the credit dries up? Well, the homes don’t get finished. The boom goes bust.

So, we can see that a result of the artificial credit expansion leads to an increased demand for short-term loans which drives up the associated short-term rates. But we also know that the Federal Reserve is actively raising the Fed Funds Rate, effectively decreasing the money supply growth. The Fed has come to grips with reality that price inflation is not “transitory” as they once insisted. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell made it clear a few weeks ago in a speech at Jackson Hole that he is on a new mission to curb inflation2:

“The [Federal Open Market Committee] is strongly resolved to bring inflation down to 2%, and we will keep at it until the job is done.”

As the Fed is trying to get a handle on the price inflation mess they created through their monetary inflation over the years, they are raising the Fed Funds Rate, putting further upward pressure on short-term rates. Arguably, the Fed isn’t raising the rates high enough to have any real impact on price inflation. But considering the economy is hooked on cheap money like an addict is hooked on heroin injections, any slight decrease in the injection of money supply will likely be just enough to spark a crash. So, it shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone that the economy goes into a recession when the injection of new money is suddenly choked off.

In that same speech, Powell went on to say,

“No one knows whether this process will lead to a recession or, if so, how significant that recession would be.”

Oh, we know. The question is, what can we do to prepare for the coming pain? Well, we can accumulate savings. Savings are critical for recovering from a recession. And once the bust hits, we must allow the clearing out of the malinvestment so that the accumulated savings can be employed to realign capital into proper investments. The cries for bailouts will be loud. But the cries must be resisted.